Södertälje konsthall

Texter

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Texter

Embracing the mystery

Av Magnus Bärtås, Fredrik Ekman

Relaterat

At the end of 1934, André Breton invited Roger Caillois to show his cabinet of curiosities. This included a Mexican jumping bean, which both were deeply fascinated by. Caillois was a versatile scholar who was interested in surrealism and aesthetics in general. Breton led the surrealist movement, over time almost as a dictator; he was the one who decided who could call himself a surrealist and who didn’t have the right to. His moody attitude made life uncertain for the surrealists, one week you were in this men’s club, the next week you were out. After the meeting when they studied the bean, Caillois was out in the cold, but it was voluntary.

Mexican jumping beans can be bought in toy stores. They are not actually beans but small fruits that start to move when you put them in your hand. Inside the fruit is a butterfly caterpillar that reacts to the heat with muscle twitches. In 1934, when Caillois and Breton observed the bending of the bean, these causes were probably not known. Caillois suggested that they should open the bean with an incision to investigate what was going on. Breton refused. Opening the bean would destroy the miracle. All our fantasies would come to nothing. Chance and unpredictability were for Breton important poetic forces in existence. What Breton perceived as a positivist stance, a rationality of Caillois – his willingness to lay bare the mystery and seek an explanation – went completely against his own impulses. The keys to the human psyche are to be found in the unknown, the irrational, the unconscious, in dreams and in mental illness, Breton believed.

On December 27, Callios announced in a letter to Breton the reason for his defection from the Surrealist movement: there is no conflict between investigation and poetry. The marvels exist in the world and nature itself has a wonderful aesthetic ability, which actually is deeply irrational. His own collection of minerals exposed, he believed, that nature indulges in aesthetic excesses. Think about the coral, Cailois suggested, which “must combine into one single system everything that until now has been systematically excluded by a mode of reason that is still incomplete.”

Caillios turned his back on Breton and came three years later to form the Collège de Sociologie in Paris with George Bataille and Michel Leris, to investigate the sacred in society, which included shamanism, magic, sex, ceremonies, festivities and analysis of the growing fascism and its essence. Caillois devoted himself to what he called a ‘diagonal science’, a science that cuts through many disciplines and where also poetry functions as a method of investigation. From his own collection of minerals, he later concluded, that the beauty and at the same time regularity that the patterns of exhibit has no rational ground. And according to Caillois, the mimicry ability of insects, for example the dramatic patterns of butterflies, is not an evolutionarily developed survival strategy, as was previously thought. Nature shows an amazing record of ”art without artists”, as Caillois put it.

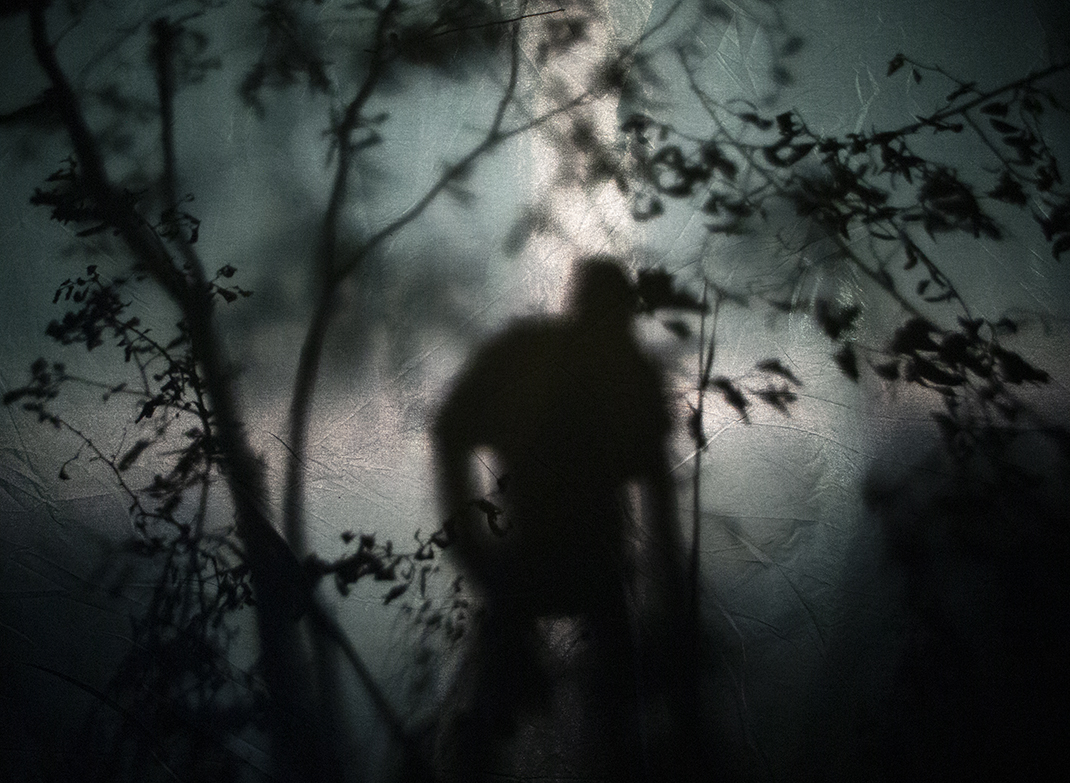

The myth of a shy, wandering ape-like figure has existed in North America since ancient times and is an inherent part of American-Canadian folklore. Millennial rock inscriptions in California depict hairy giants with ape-like hands and feet. Stories of such creatures were passed down from indigenous peoples in many places, from Alaska to California. The indigenous people often called them Sasquatch and believed that they belonged to the spirit world and had the ability to materialize and disappear.

In northwestern California in October 1967, the two rodeo riders Roger Patterson and Robert Gimlin set out in search of such a creature, which they call Bigfoot. They ride in the Six Rivers National Forest, a vast and arcane nature reserve. There, in the riverbed of Bluff Creek, nine years earlier, strange footprints had been found that no one could explain. The men carry a 16-millimeter camera and travel upstream on horseback. After passing large fallen trees with exposed roots, they come to a lot where dead trees have been piled up after a previous flood. Here they saw a figure sitting bent over by the water on the other side of the river. Patterson’s horse rears as Gimlin rides across the river in the direction of the creature. Patterson manage to calm his horse and get his camera out.

This is Gimlin’s and Patterson’s story. What’s left for the world is a minute of grainy footage showing a tall, hairy figure with swinging arms disappearing into the forest with quick, agile steps. At one point it turns its gaze towards its trackers and shows a hint of breasts, it is probably a female.

The film received enormous attention; no other motion pictures had given such a vivid representation of Bigfoot. 31 years after the incident, a man claimed to have played the role, to have been equipped with a modified gorilla suit by Gimlin and Patterson, made by costume designer Philip Morris in Hollywood, and then completed his mission by the river.

In the same year, 1998, Jeff Glickman, a well-known forensic examiner, published an extensive report on the film. Glickman had spent three years analyzing it in detail. The first copy of the 16mm film, stored in a temperate bank vault, was flown to a lab in New Jersey where a digital copy was made. Photographs from field surveys in 1972 were compared to the film to determine the size of the dead trees at the site, and thus an estimate of the creature’s length was made, which Glickman was able to determine with great accuracy: 222.5 cm. In 2015, there were only 2,800 people out of the world’s population of 7.4 billion who achieved such a height. In 1967 there were very few people that tall. Through image analysis, Glickman calculated the creature’s body mass, the length of the arms, the body mass of the legs and torso, and concluded that the creature would have weighed 887 kilograms. Glickman also stressed that the movement pattern the creature exhibited would be impossible for a human in a gorilla suit to perform. According to the forensic examiner, to stage the event in a credible way would have required ”in-depth knowledge of primatological anatomy and materials science.”

In southern Mississippi, similar legends abound about wild men in the woods flourishes. A circus train on its way to New Orleans is said to have derailed in the swamps near Chatawa at the turn of the last century. The train carried creatures out of the bestiary of cryptozoology and all of these rare specimens were believed to have been killed in the derailment. The cage that housed a great ape was now empty. A few weeks after the accident, the nuns at the Catholic girls’ school St. Mary of the Pines said that they saw the ape in the forest. Over the years, there have been testimonies at St. Mary about sightings and traces of a large, shy hairy creature in the surroundings. Even today, people talk about the mysteries of Chatawa. Hap Philips, a man who lives in the area says in an interview with Thurfjell that Chatawa is a place of supernatural phenomena, an area, where many doors are open ‘for all kind of things to come in go out.’

Jeff Glickman devoted three years of research to the grainy Bigfoot film from 1967. He may have risked his reputation as a forensic expert, but he was driven by a desire not to settle for the myths that’s has left ‘anecdotal record through man’s collective memory,’ as he puts it. He insisted and did what Breton refused, he cut open the bean. And the scientific investigation did not kill the story, instead it gave new fuel to the myth. Our fantasies about the forest monster took on new contours, and Roger Caillois was right after all: there is no real contradiction between research and poetry.

Johan Thurfjell, who has long dealt with the Bigfoot myth, also seems to perceive no such contradiction. He has created his own version of Caillois’s diagonal research, which includes optical experiments: shadow theatre, laterna magica and camera lucida techniques and renewal of old illusion numbers from the theater such as Pepper’s Ghost with projections of objects through mirrors. With the help of a data bank, he has sought out locations of Bigfoot testimonies and documented them in aquarelle, like a Sunday painter or an old-fashioned reportage cartoonist (Testimony, 2010). He conducts field surveys, audio recordings and interviews with people in the Chatawa area.

Experiences of the unknown often give rise to fundamental questions of perception. As in the encounter with a work of art, we must ask ourselves the question: what am I really seeing? And how shall I speak of that which is seen but never seen? Or, as Chatawa forest resident Hap Philips says: ‘what you see but don’t want to see.’

The desire to portray this borderland is still strong wherever we are in the world, which has given rise to forms and figures that have taken on a life of their own. We seem to need monsters – create them, portray them, tell about them – perhaps ‘to keep us humble, or to keep us aware’, as Hap Philips puts it.

Johan Thurfjell’s diagonal research does not, however, have a scientific or journalistic purpose. The results of his investigations – artistic utterances – cannot be said to be ‘about’ a subject. The work of art may revolve around a subject, but its main function is stipulative, instituting – to give us the opportunity to enter the subject and experience it. Therefore, the work of art must in some sense also embrace the mystery. When we play his board game Chatawa, where we move within the habitat of the Chatawa monster, a tension of both anticipation and menace is created. We think we are getting closer to the solution, but we risk being disappointed at any time. On the way to a decision, we as tracers must use our instinct, our tactical ability but also our sense.

In Japanese culture, a rich visual world has been created around boundary creatures that move between life and death, day and night. The Japanese manga and anime culture continues to build on ancient depictions of ōmagatoki – ‘the hour of encounters with evil spirits.’ In this passage between dusk and night, the blue hour, the boundaries between the living and the dead are porous. As the shadows grow long and diffuse and the last light of day soon turns to darkness, yokāi figures emerge like characters in the Swedish folk beliefs as vättarand oknytt.

Johan Thurfjell’s tin lantern with blue glass refers to the Japanese tradition of using blue paper lanterns when telling ghost stories. During the Edo period, the aristocrats gathered in the summer to cool off with the chills that a horror-filled history can bring. They lit 100 blue lanterns and after each ghost story a lantern was extinguished, finally there was only one lantern left whose last gasping glow cast long ghostly shadows on the wall. If one last story was told and one last lantern extinguished, the dreaded ao andon – the demon of the blue lantern – was awakened.

Johan Thurfjell’s works are intimately connected with the history of phantasmagoria, a history of illusion tricks, spirit images, visions, light phenomena, séances, ghost voices, tappings, automatic writing… In Phantasmagoria (2006), the art historian Marina Warner links this history to the development of technology, where each invention – the photograph, the film, the telegraph, the tape recorder, the wax technique – trace the invisible and the unknown. In the formations of our ideas, agreements gradually arise, forms give rise to forms that are engraved into our collective consciousness. Soon many of us agrees that a chubby baby can carry a bow and shoot arrows of love, that the Gothic bow signifies aspiration, ethereal lightness and divinity, that an alien has an oval head and large dark eyes without pupils.

Even nature can function as a phantasmagoric theater. Chatawa’s swamps and thickets seem to possess an unusual, powerful ability. Constantly, new sprawling scenes arise: the branchwork is rearranged, the beard moss moves and climbing plants throw out new tendrils, the images change. It happens that an unknown creature has dragged away a prey and created a passage in the thorny undergrowth. The river’s sandbeds and water currents constantly sculpt the driftwood into new formations, pile it up, cross it like a giant Mikado game, dissolve it, and pass the pieces on to the next unseen sculptor. Do these phantasmagorical creations only have a meaning when we look at them? Or do they carry their own intentions and their own symbolism?