As early as 1972, Hasior had his first exhibition in Södertälje konsthall together with Jerzy Beres´. The two were then counted as two of Poland’s foremost artists. Hasior had made his debut in Sweden at the Moderna Museet four years earlier and had already met with much attention. Before Södertälje konsthall received the exhibition with Hasior and Beres´, it had been shown in Louisiana in Denmark, but then together with Robert Indiana. In a script for the narrator, Södertälje, written by curator Ingvar Claeson dated 18 October 1972, the superlatives hail “It was fascinating to see the world-famous Pole for two weeks, day and night, strolling around inside the art gallery, trying out his pictures, changing, complementary, add, subtract, mumble a little resignedly about the ceiling height, completely sonic cut off some of the flags, sew them together again, one meter shorter.” He summarizes public comments “Hasior had an exhibition at the Moderna Museet four years ago, which people still talk about as ‘fantastic’, ‘fascinating, mysterious’, ‘you can never be this good yourself’, what a colossal feeling man has for the connection between the artwork’s form and message ”,“ can we not get him to Stockholm again! ”,“ they have better exhibitions in Södertälje, than in Stockholm! etc. ”.

In connection with the exhibition at Södertälje konsthall, Hasior offered to create a sculptural work on the canal slope towards the lake Maren. It was the beginning of an intensive and long-standing collaboration with the municipality, Södertälje konsthall and the artist.

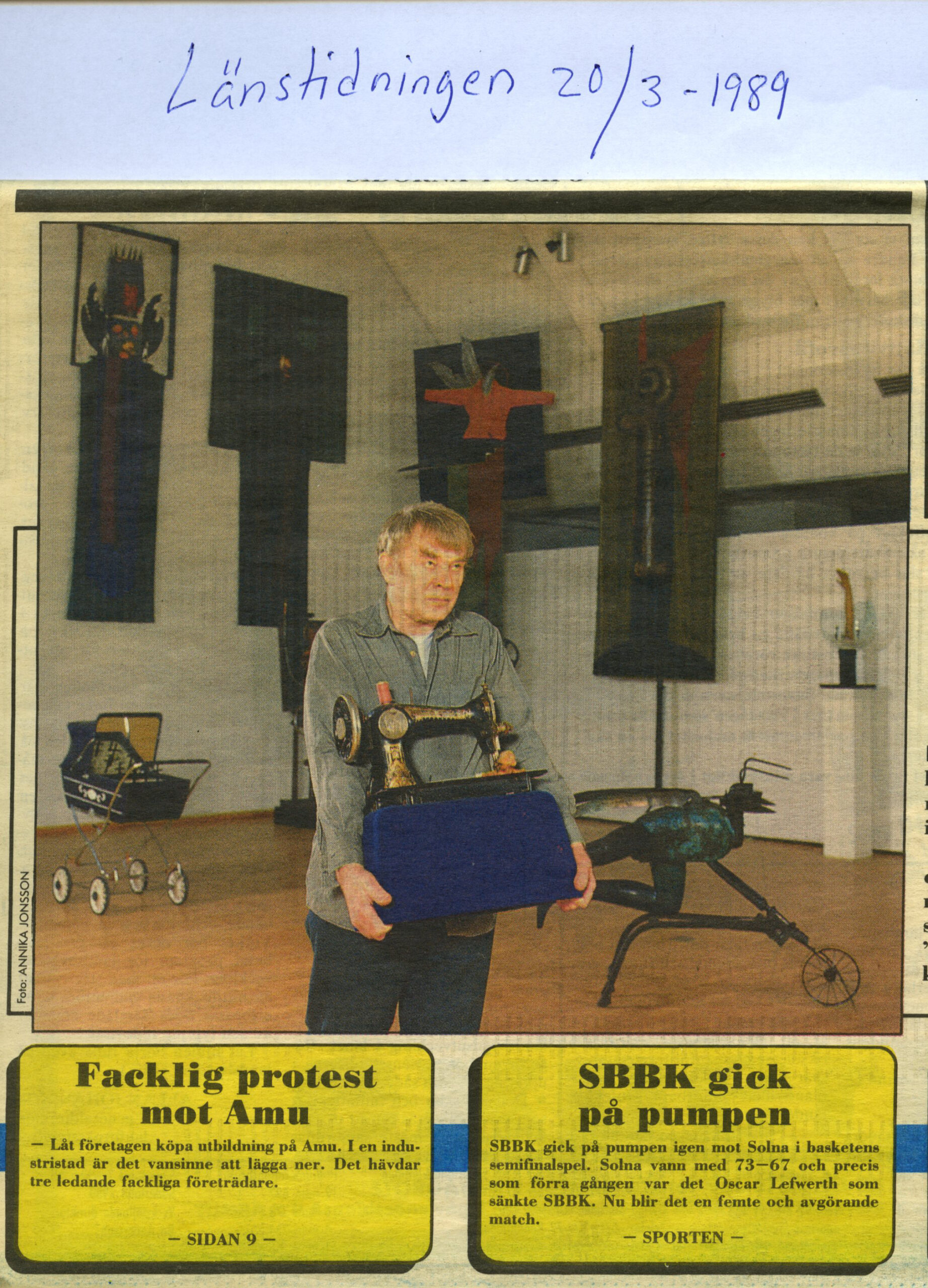

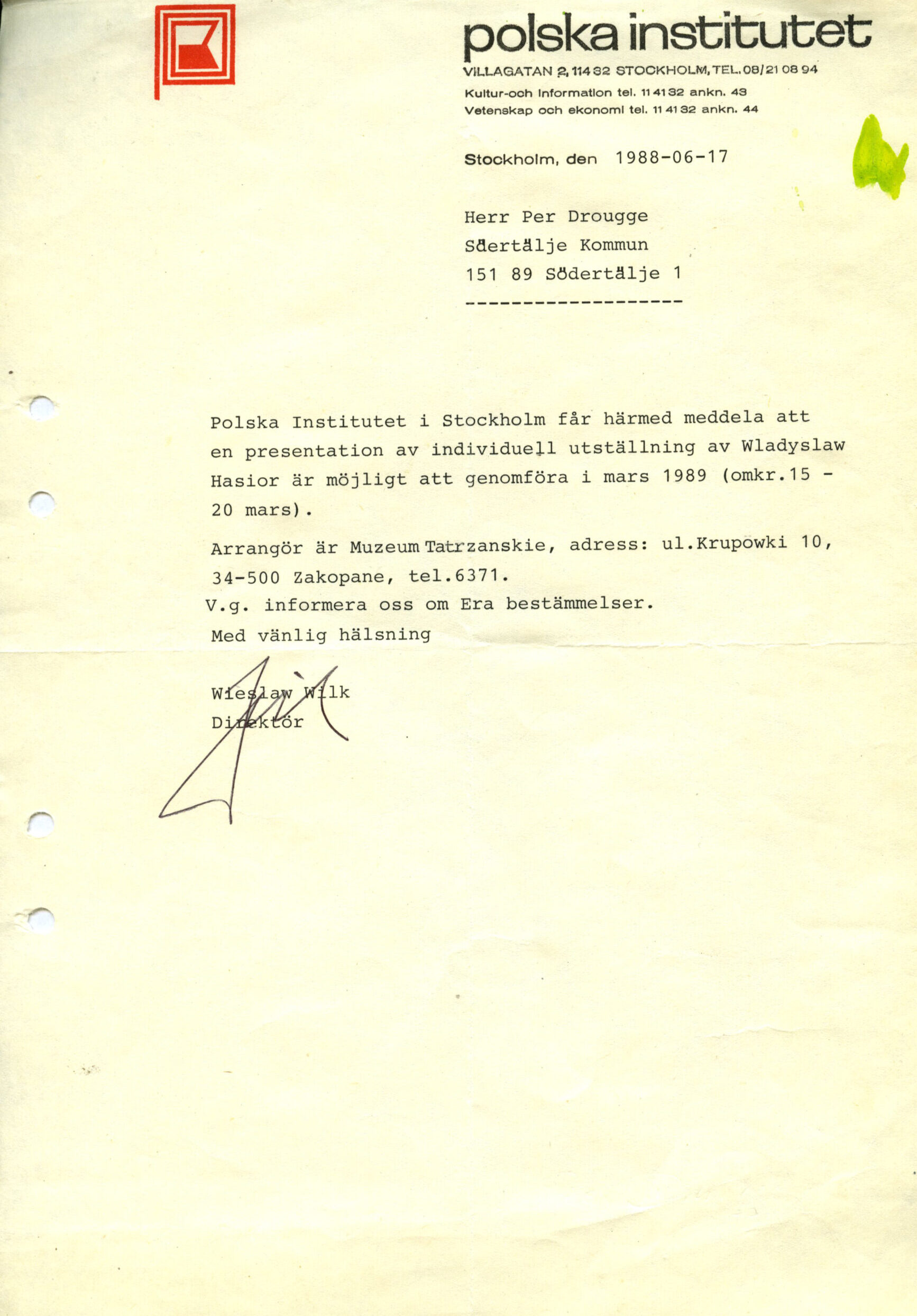

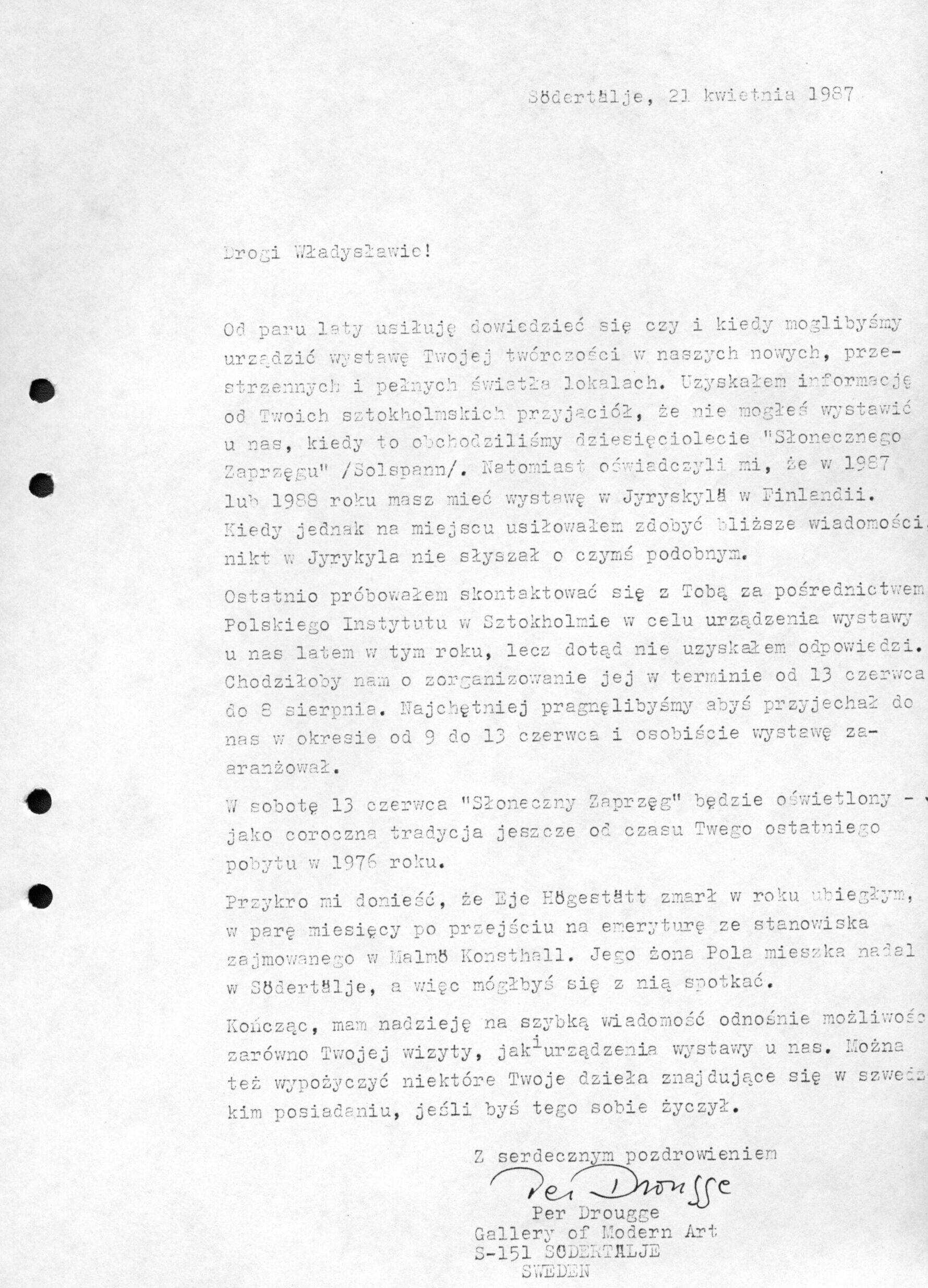

Södertälje konsthall director Per Drougge visited Hasior on several occasions in his hometown of Zakopane. During a visit in 1987, the artist was in an intense creative period, the creation of his own one-man museum Galeria Hasiora. Now the promise was made of an exhibition in Södertälje konsthall 1988-89, in connection with a tour. Drougge proudly writes in a letter dated 9 August 1988 after a visit to Hasior in Zakopane, that the negotiations for a separate exhibition were finally crowned with success. Financial support is received from the Swedish Institute and negotiations with the Muzeum Tatrzanskie have begun. One hopes for an exhibition in March – April 1989. At this time, Hasior has long been widely famous and noted for his metaphorical and ambiguous assemblages, his standards (banners) and his relationship to sculpture and the four elements, especially fire. Drougge summarizes the artist in one of the short texts in the exhibition catalog.

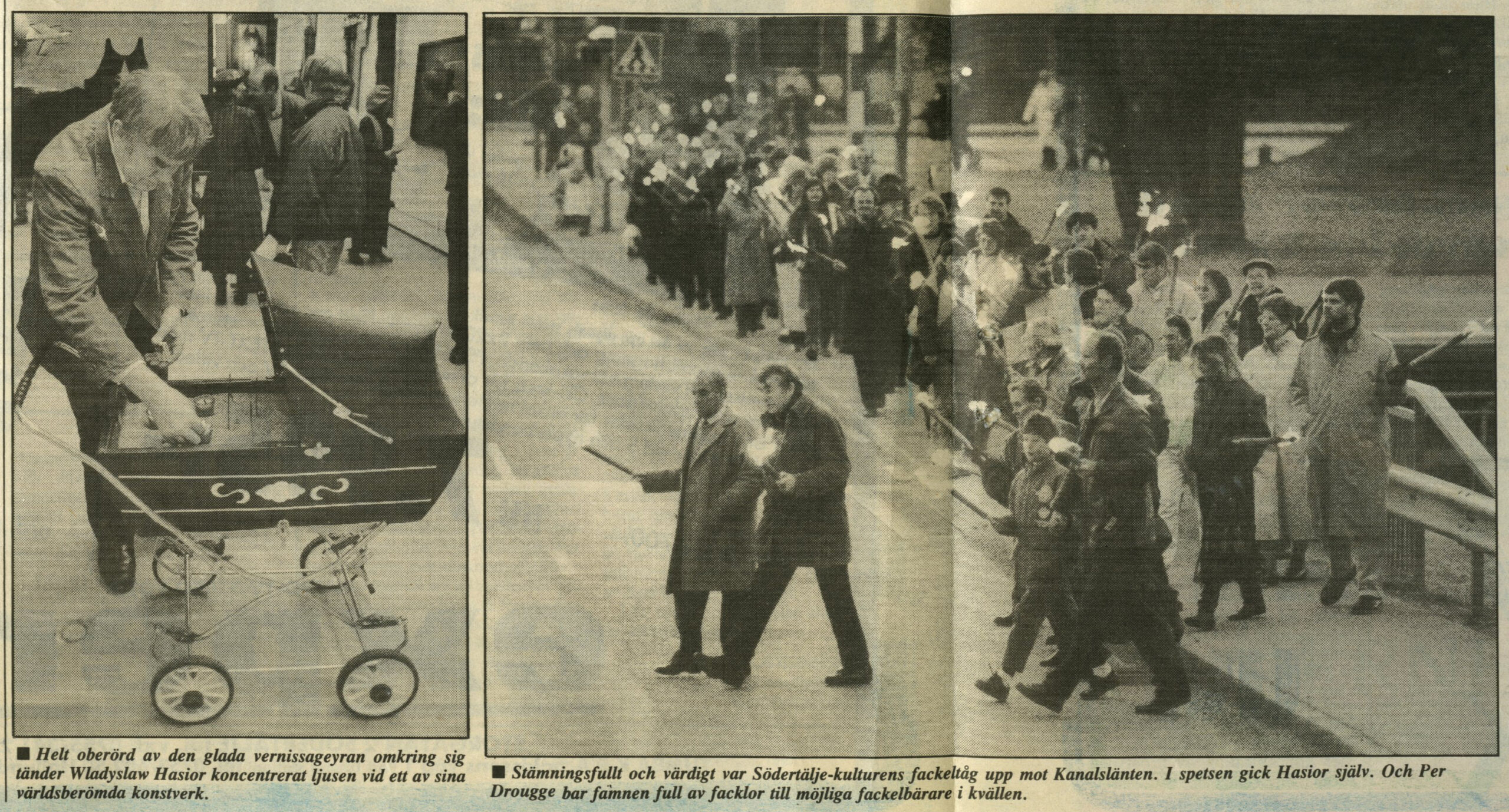

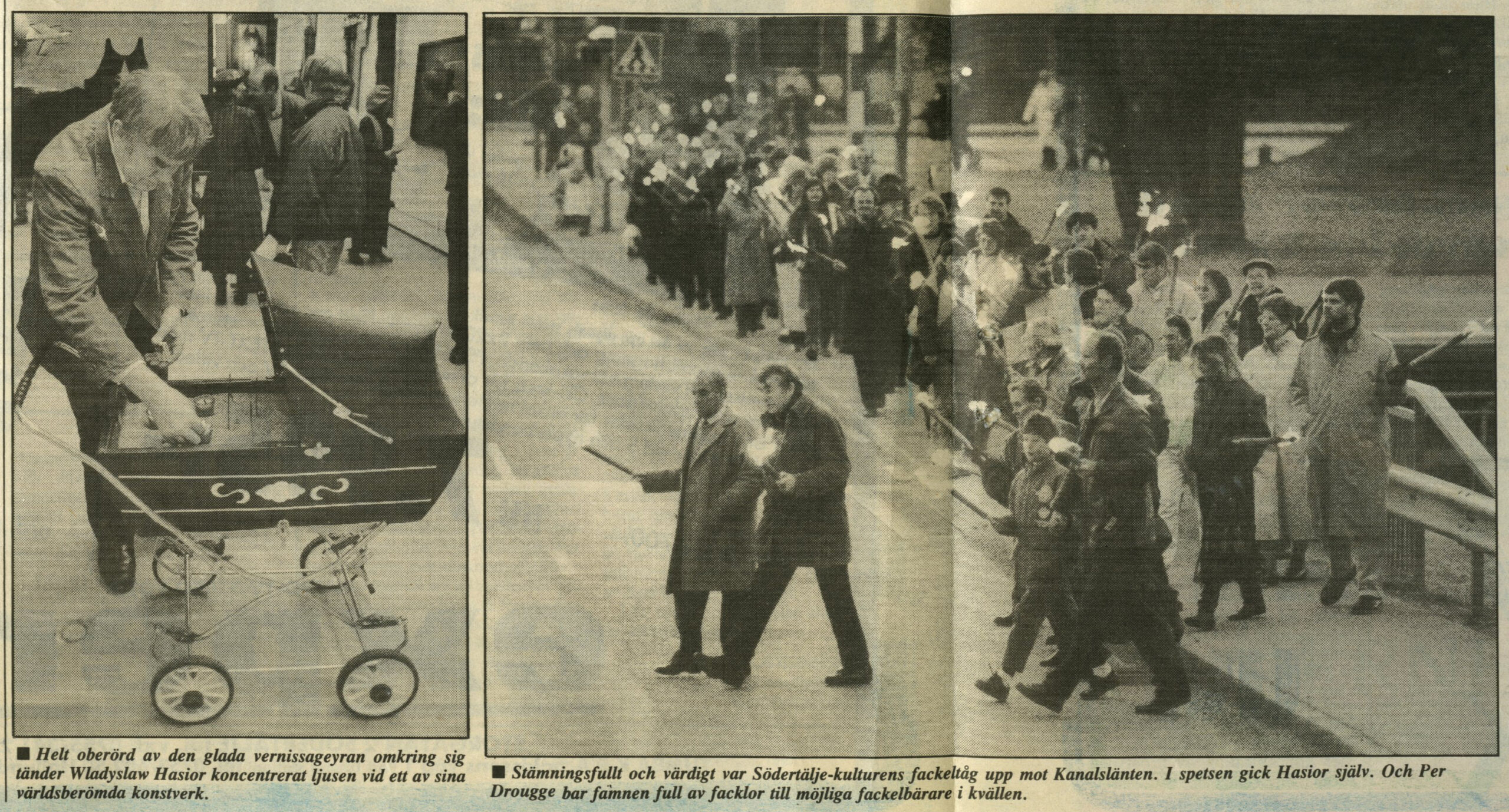

“Hasior is the ingenious engineer of his own exhibitions. But he is also the officiant in these; priest and shaman, poet and pyromaniac. Quiet, secretive, he walks around with his fireplaces, lights magic fires, colored lanterns, lights up and burns down, but also lights still altars and burial flames.”

Södertälje konsthall had a long tradition of collaborations with artists from Eastern Europe. Drougge further writes “The opening, which these days seems to take place from the east, is actually reflected in the Hasior exhibition’s journey from Zakopane over Moscow and Tallinn to Södertälje. A few years ago, Hasior – the Prometeus and pyromaniac of this visual art could hardly have been shown in Moscow, least of all in Tallinn – only the early era of perestroika and glasnost (openness) could have made this possible.” The exhibition then went on to Helsinki.

For 14 days, Hasior worked on the installation of his exhibition. He worked quietly and devoutly side by side with his female assistant, as in an ongoing telepathic communication. It seemed as if they were working around the clock. I noticed this when, as a young student in the cultural studies line, I sometimes worked at Södertälje konsthall. One day when I was about to open the exhibition, I was surprised when he was already there. Hasior spoke French. I approached him and said Bonjour monsieur Hasior! He looked tired, looked down at the floor and greeted back, though very quiet.

At the entrance to the art gallery, a table with chairs was placed. At one point, Drougge and Hasior sat there, engaged in a lively discussion. Both smoked. My even younger colleague then came forward and reprimanded them. Excuse moi! pas fumé si´l vous plait! (do not smoke). It was forbidden to smoke in Södertälje konsthall.

This was probably one of the most engaging exhibitions in the history of Södertälje konsthall. Visitors came to see the exhibition, and came back several times. Many wanted to talk to the artist and discuss. There was a lot of emotion in the air. Conversations about politics, oppression and religion. The artist was often highlighted by visitors as a universal genius. Should one talk about the artist and how he thinks, or should art speak for itself? An issue that could provoke debate. The strong expression of the works of art touched in many ways.

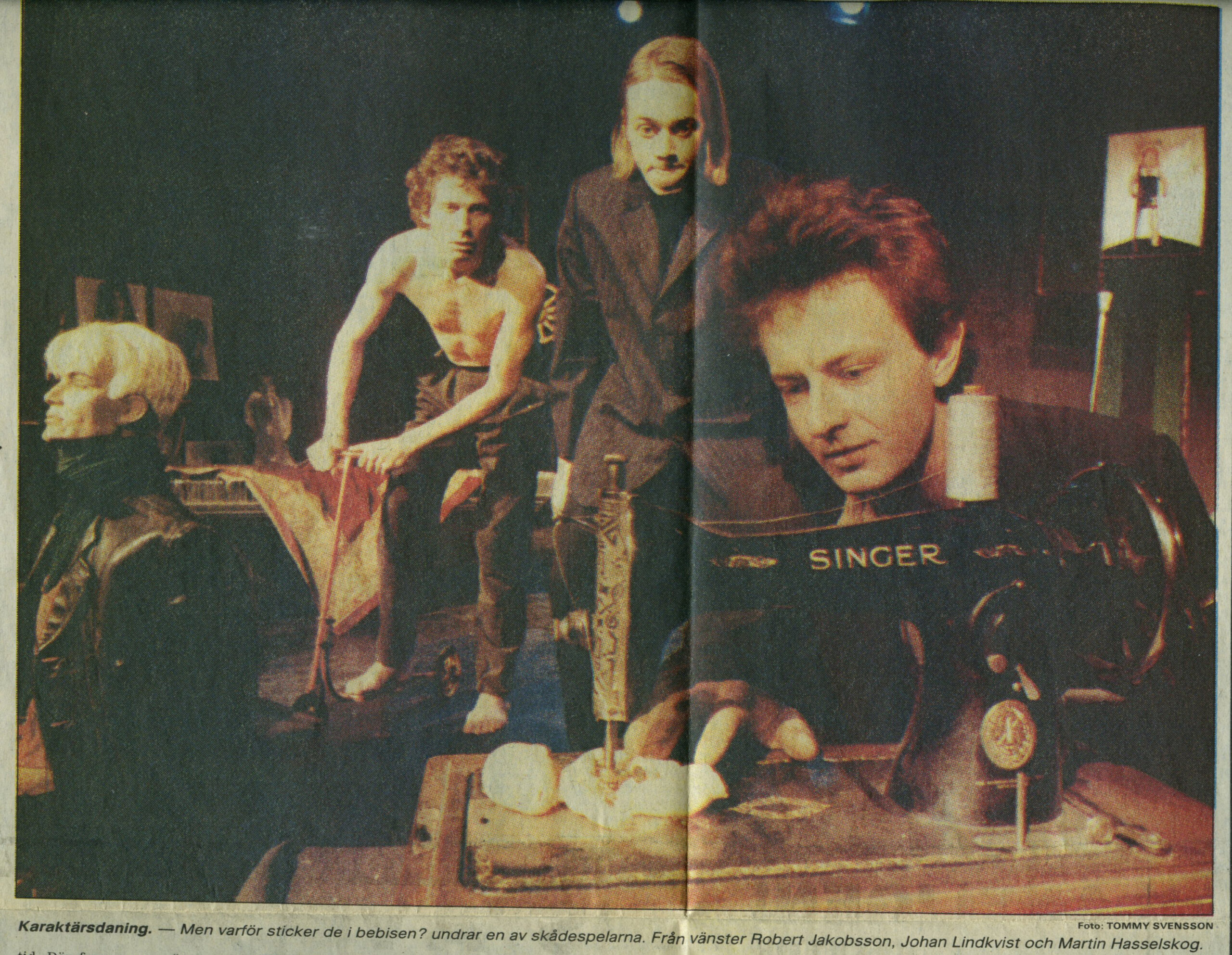

One who seemed to have been deeply touched was the actor Robert Jakobsson from theater Albatross. I DN (Dagens Nyheter). Culture 16 February 1991 Karin Berglund writes “When Hasior exhibited in Tallinn a few years ago, Robert sought him out and told him about his dream of playing theater with the exhibition as a stage room. The sculptor was moved and said yes. – Then I followed him to Södertälje, Helsinki and Brussels and played in his exhibition, says Robert. That’s how “The Burning Man” grew. The one-man show with the episodes written by Jakobsson 15 of his own that was played in Södertälje konsthall was originally about 40 minutes long. With the artist’s permission, the artworks were included associatively in the performance and in Södertälje konsthall, three performances were played with “The Burning Man” or as it was then called in the program “The Baptism of Fire”. Hasior showed his appreciation by standing up and applauding. Theater Albatross, led by Robert Jakobsson, developed and varied the play for several years. With the artist’s blessing, Hasior-inspired props were used or manufactured.

Wladyslaw Hasior lit his candles. However, the cigarette glow fell. Performances that took place became very burning and heartfelt. The conversations inside, even those colored with fire, became many.

Sources: Södertälje konsthalls archive folder, text and compiled by Anneli Karlsson