Södertälje konsthall

Portal

2022

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

2022

The Seeping Sun

By Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian,

29/01 – 12/02, 2022

Related texts

Externa länkar

January 29 – February 12 2022. Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 12-18, Saturday 12-16.

Beardless, moon-faced figures with silky skin, almond-shaped eyes, and crescent eyebrows. Such were performers: dancers, musicians, and wine pourers – or saaghi in Farsi – depicted in poetry and painting when the Qajar dynasty ruled in Iran from 1789 to 1925. At that time, sexual exploitation was closely linked to these performative acts, and the performers were thus often reduced to sexual objects. Simultaneously, their beauty was celebrated and set an ideal, which was loved abundantly by populations from the eastern borders of the Mediterranean Sea to Central Asia. With that, a behavioral norm centered around non-binary expressions of gender, and non-gendered desire was popularized.

With 19th-century British and French colonialism and imperialism in South-Western Asia and North Africa (SWANA), these behaviours had to shift. In the intruded states, the colonizers implemented a binary concept of attraction specifically between the female and male. In this paradigm of ideas, sexual relationships were only accepted if they were between the different sexes, and in image culture men and women had to be portrayed differently. The nation was also gendered: an ancestral motherland protected by an administrative and militarized fatherland – the new modern state, where people acted, spoke, and dressed differently.

In many countries in the SWANA region, the middle and upper class attended missionary schools. They grew to speak French and English, which made them even linguistically separate from the working class. This education also turned them towards Western European ideals. In Iran, however, the 1979 Islamic Revolution changed the country drastically. As an act of anti-Western imperialism, all cultural Western imports were banned. Still, they remained available, since they were desired and looked up to. Meanwhile, with the Islamification of the country, the saaghi who poured the wine was banned and their name now translated into dealer. Just like alcohol, much music and film became illicit in the country. That being so, the saaghi of sound and moving images was born, the filmi or the videoyi.

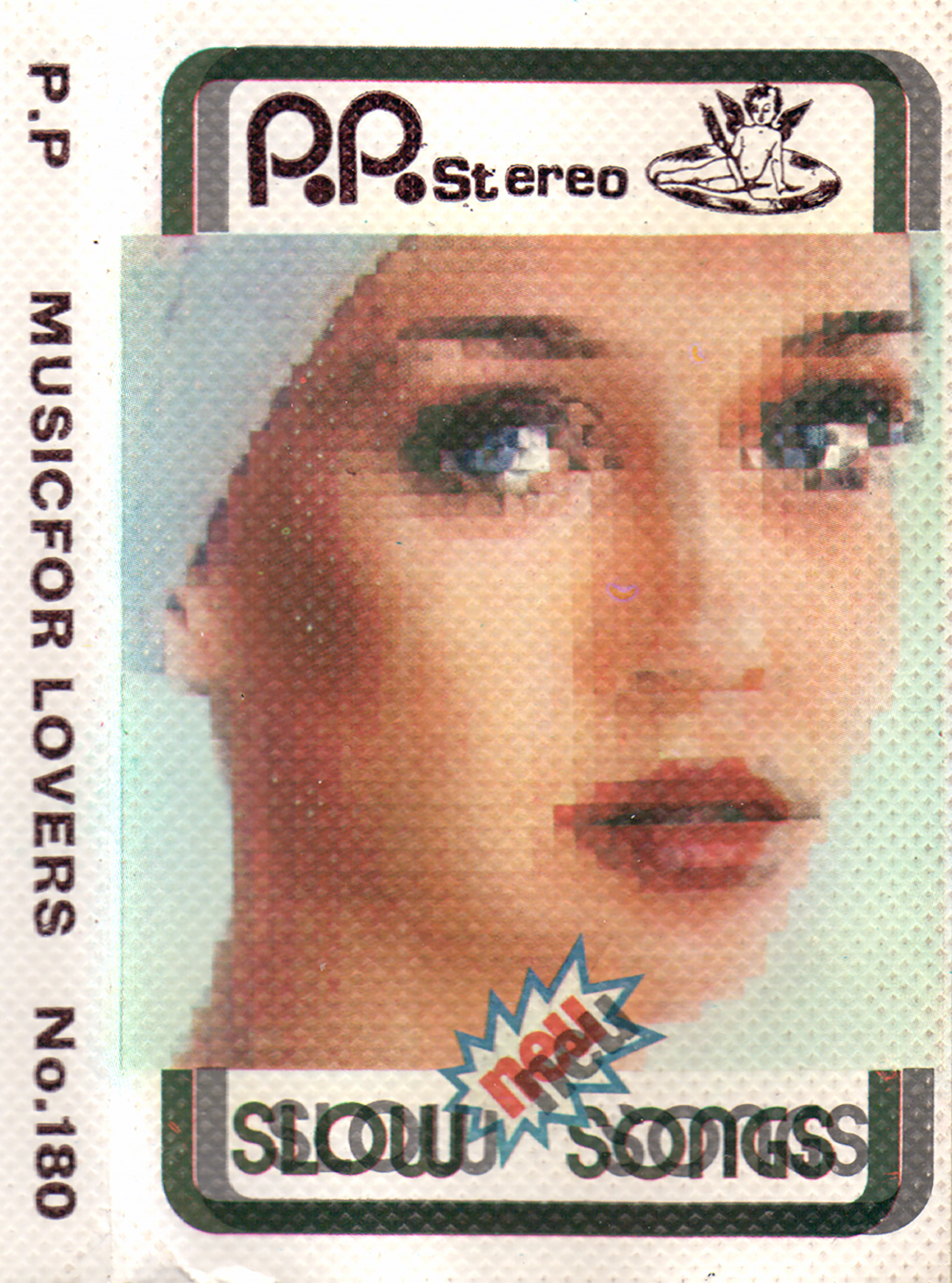

In our exhibition, The Seeping Sun, we present three short stories on how these colonial ideals and anticolonial frameworks manifest in everyday life. These stories are accompanied by a rare assemblage of reproductions of vinyl and cassette covers from the 1950s-90s, from Egypt, Iran, and Lebanon. They depict performers such as Googoosh, Onik, Oum Kalthoum, and Sabah.

Nour Helou, art historian and writer

Afrang Nordlöf Malekian, artist and writer

Agga Stage, graphic designer

Saïd Helou, Arabic language editor

Soroor Notash, translation English to Farsi

Sylvie Robinson, English language editor

Edwin Safari, English language editor

Jeremy Tavitian, English language editor

A special thanks to Södertälje konsthall, Joanna Sandell, Diana Agunbiade-Kolawole, Amr Hamid, Elnaz Khorasani, Chico Records, and Johan Söderbäck.