Södertälje konsthall

Texter

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Texter

Interview with Nour Helou, Afrang Nordlöf Malekian

Av Daniella Maraui

Relaterat

Interview:

Tell me about the exhibition, what are you currently showing at Södertälje konsthall?

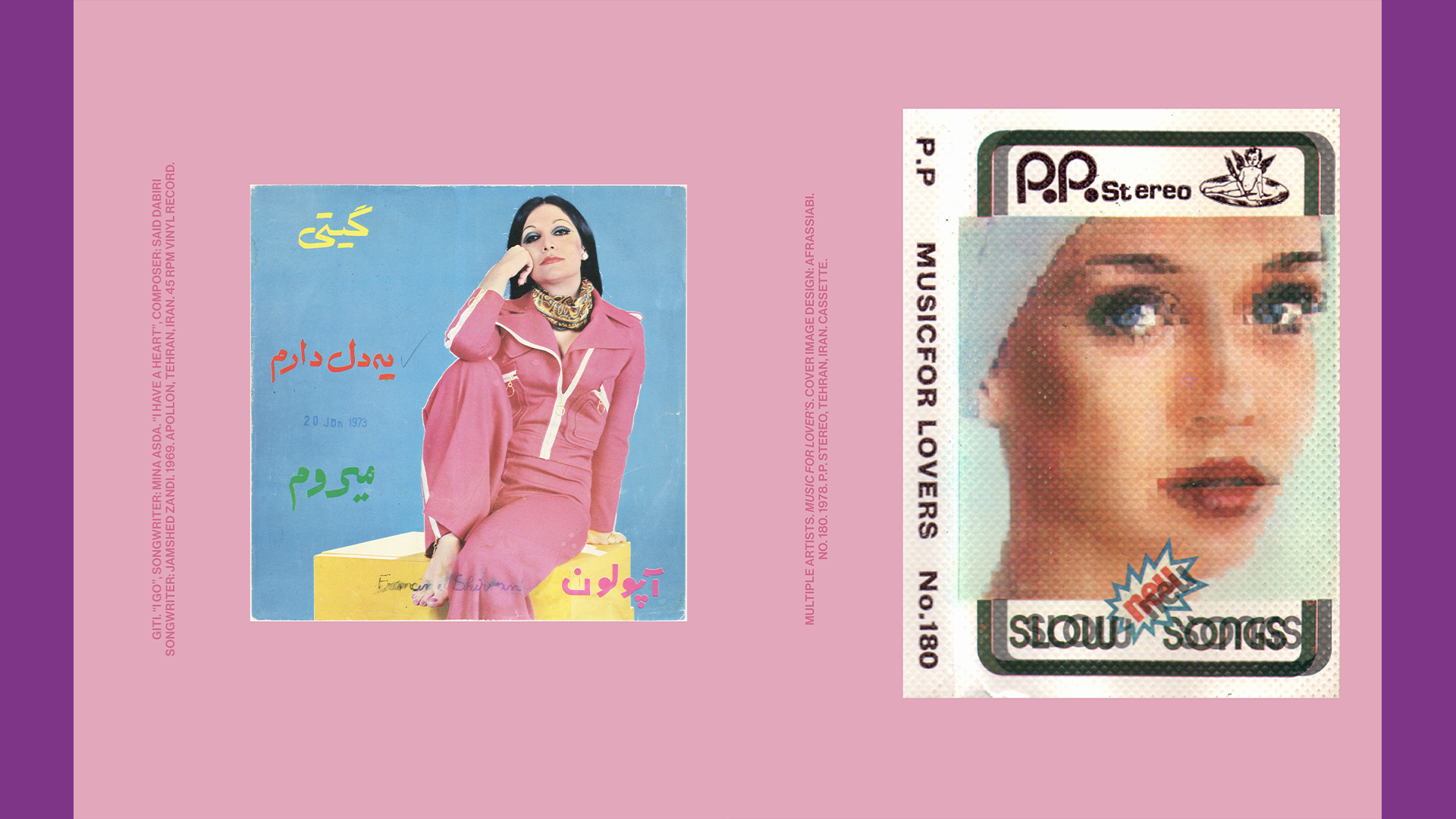

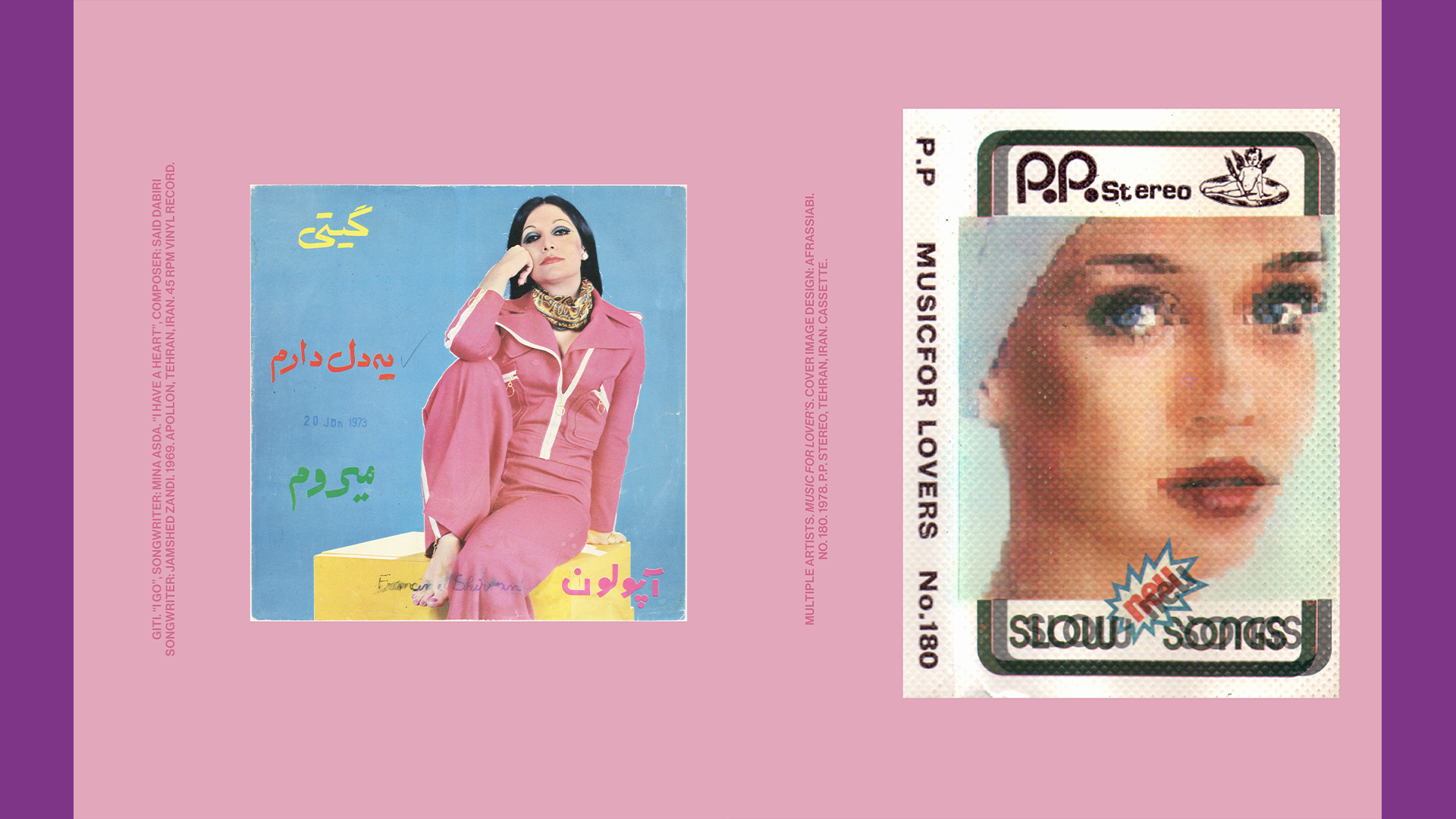

Nour: The format of this show consists of three stories that I wrote together with Afrang. We presented them with acurated selection of vinyl and cassette reproductions from the 40s-90s from Egypt, Iran, and Lebanon. To find this group of images we looked through various archives, visited vinyl collectors, and went to different record stores.

The reason why we chose those images is that they bare the same non-binary beauty aesthetics as the ones that can be found in hand-colored photographic prints from the mid 20th cenutry and later, which can be traced back to a history of fluid beauty standards in paintings from the Qajar-era in Iran that ranges from 1789 to 1925.

During that Qajar period, as can be seen in the paintings, the ideal of beauty for a person related to attributes such as a moon-face, big almond-shaped eyes, crescent eyebrows, and rosy cheeks. This history is one that we have been working with since the beginning, since our first exhibition, The Eclipse of the Fe(male) Sun, in 2020 at Tegel in Stockholm.

We had worked then, with Arab Image Foundation hand-colored photographs, an archive for photographic objects fromSouth-West Asia and North Africa, in Beirut. We kept on working with those photographs for our second exhibition together, which is entitled, Shape-Shifting Flickers of Love, from 2021 at Folkets Park, in Malmö. It was exhibited again at Tensta konsthall in Stockholm as part of the group show called, Phantoms of the Commons. In Södertälje konsthall, we are no longer working with hand-colored images only, but rather with images that hold these same aesthetics.

How are all the three shows, The Eclipse of the Fe(male) Sun, Shape-Shifting Flickers of Love, and now, The Seeping Sun connected to each other?

Afrang: The core material is hand-colored photographs from the SWANA region [South-West Asia and North Africa]. We are studying the aesthetics of gender in the photographs. The aesthetics can be traced back to Qajar-paintings as well as colonial constructs of gender and race. A study that helps us to reflect on current behaviors, images, and music that are part of our day-to-day life. These everyday events on how these aesthetics shape our lives—from having your passport picture taken to visiting a mosque—are presented in each exhibition.

Why is it important to discuss topics like anti-colonialism and non-binary expressions in relation to each other in the SWANA-region?

Nour: I would not say that we are discussing anti-colonialism, but that we are trying to decolonize a beauty norm. We are looking at pre-modern beauty standards, but also at how they have changed and how they exist today in countries that have been colonized or imperialized. It is not only about looking back, it is about situating these past norms and examining how similar, and yet new ones, manifest themselves today, and how they impact our behaviors, in our beings, our language, in how we dress, in our performativity.

The first exhibition [The Eclipse of the Fe(male) Sun (2020)] is centered around beauty standards and the second one [Shape-Shifting Flickers of Love (2021)] looks at how they impact our behaviors in relationships. In the second exhibition, we also focused a lot on architecture and gendered spaces, like the mosque, and an opera house that was built by the French in Lebanon. The third exhibition [The Seeping Sun (2021)] is really about how this layered history of pre-modern beauty standards, followed by colonialism displays itself today. How this impacts a young person growing up in Lebanon or Iran, and dictates our agency as people who have to exist in such societies.

For this project, you picked famous singers or performers, how are they related to the saghi that you have written about in the stories?

Afrang: It is an overarching research, the paintings that we studied from the Qajar-era are mostly paintings of performers,like dancers, musicians, saghis, which literally means wine-pourers. It was the performers that bore these beauty standards the most and set these standards that spread to other figures. This history of non-binary beauty is also paired with the perception of performers as objects of desire by the crowds they would entertain. Which is a very uncomfortable position.

Could you even say that the singers you have chosen for this exhibition, are also just reduced to their looks since theyexhibit these beauty standards?

Afrang: They might be reduced by some, which means that their value is reduced. In other words: in colonial ideas of gender, feminine or female aesthetics equals loss of value.

The beauty standards that were present in Iran in the 18th century translated, through modernization, into the beauty standards of the female. Yet a complete translation was unsuccessful. The female artists and a few male ones in The Seeping Sun carry the pre-modern appearances. Pre-modern ideals survived modernization. Therefore, labeling these aesthetics as pre-modern is wrong since they still are practiced in the modern era. Non-modern aesthetics or anti-modern aesthetics would be a more accurate term.

Nour: There is also an aspect of forced labor that is constantly taking place. In pre-modern times, there was sexual labor associated to performers. There is also a forcible change in aesthetics, whether it is within internal political structures or external, with imperialism. This superimposition of structures has led to the differentiation and binarism of these new beauty standards.

What is your driving force for this project?

Afrang: To understand how we are makers of history, one that maybe is not part of the dominant narrative of a nation, but rather one where we can be in conversation with each other, with people showing resistance against oppressive structures. It could be women, it could be non-binary people, it could be gays, it could just be someone going to school. That is who I am trying to be in conversation with.

Nour: For me, it comes from a desire to gain some insight into gender constructions in Lebanon and the region, to understand myself in the society I grew up in, in these power dynamics between Lebanon and France, the colonized and the colonizer.

Afrang: In The Seeping Sun we explore the character of the people who grow up within this ambiguous power structure. For instance a kid who is going to school in Lebanon and does not find Arabic as poetic as French, meanwhile also feeling estranged by the French language itself.

This could be related to the Islamic Revolution 1979, that you have written about for this show, how the people have a love-hate relationship towards the West. It is something that I think one can see in a lot of South-West Asian countries. This admiration for the West, wanting to be like them, but also despising it. It is complicated and hard to explain, especially for those who have origin from those countries, and then grow up here in the West.

Nour: I think this contradictory feeling towards the West, that is exactly why these stories exist. It is for this space that is not black and white. It is for this in-between space that is difficult to articulate, and to grapple with but also present and obvious. Everything does not have to be so binary, on various levels. Like relationships too, structures of powers are not linear, and there is a need to come to terms with them in a more fluid manner.

How did the two of you meet and decide to work together for this project?

Nour: We met in a bar!

Afrang: At Bar 27 in Badaro in Beirut.

Nour: We met through common friends, and we started talking. Afrang was digitizing and researching hand-colored photographs at the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut, and studying the same Qajar history of beauty standards I was researching at the time.

Afrang: Then I moved back to Stockholm and covid started. We then applied for a residency at Tegel, which is an art space run by curators Asrin Haidari and Maria Elena Guerra Aredal. We got that residency, so during the summer, the gallery served as a studio space. We then had our first exhibition together there in August 2020. Unfortunately, Nourcould not come because of new regulations put in place due to covid. I was working at Tegel, and Nour was working from home in Beirut.

And it worked!

Afrang: Yes! Our method was to study the images, and read theory and fiction in relation to them. We would constantly discuss the readings and images—mostly by anchoring them in everyday life situations. And bit by bit we began to write them down.

Nour: It was organic. It worked.

Afrang: And we continued with this process for the other exhibitions and new works we created within this collaboration.

Could you walk me through the process of gathering the reproductions of the LP and cassette covers?

Afrang: This is the first exhibition where we did not work with an existing archive, so we had to collect everything ourselves. We started to read about music history in SWANA. Our first musical interest was the tarab genre, which is practiced in Egypt but also in Eastern Africa, like in Ethiopia and Zanzibar.

Nour: Tarab is a double term, it relates to the musical genre, but it also means a state of ecstasy. For example, Oum Koulthoum songs that are very long and repetitive, this is tarab, and it puts you into a trance because it is repetition, repetition, repetition. So yes, we started to read about tarab and were trying to find information about album covers, specifically, and then realized that almost no one had written about this.

Afrang: We were lucky to find an Iranian scholar who was also into this, studying art history. We had a meeting with him and he told us about the history of music production in Iran. He was researching the time period that preceded the one we were examining but it was still very informative to speak with him in regards to the images. What we then did was contact people on Discogs that sell old vinyls and cassettes. One of them was Johan Söderbäck, who has been collecting rare vinyl discs from Iran. We asked to borrow them and scanned the covers. Also, Nour was in Beirut, going to all the vinyl stores she knew and scanning album covers we were interested in. I asked my boyfriend’s family who lives in Iran if they knew somebody who had cassettes, so some of the ones we exhibited are from his aunt. We also got help from an Egyptian artist who collects cassettes in Stockholm, Amr Hamid. We also went through many vinyl stores in Stockholm. We spent lots of time searching for these images. Sometimes I forget that. It is massive work, sometimes I see a cover on Spotify, and I think “oh this is a good one where can I find it”.

So what comes first, the stories you write or the images, or do you do it simultaneously?

Afrang: Simultaneously. Even when installing The Seeping Sun we removed two images. The images should never become illustrations or specific representations of characters in the stories, so that is why we work with both photographs and texts at the same time. If the photographs become illustrations they stop being vessels of imagination. In that case, the histories that these photographs can make unfold would disappear.

Why is your exhibition called The Seeping Sun?

Nour: If you go back to the Qajar era in Iran, from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th century, the symbol of Persia—and then Iran—was an image of a lion with a sun rising from above it. The lion and the sun represented the king. This sun specifically bore those non-binary beauty standards, it was itself both male and female, with a moon face, big almond eyes and rosy cheeks. Over time, as modernization took place and unfolded, the sun of this national emblem was reduced in size, and its facial features progressively disappeared. So, we used “the seeping sun” as a metaphor, to talk about how these beauty standards still make their way in, in our contemporary lives.

Afrang: In the first text of the exhibition, the one on the blue-colored print, there is a sentence where the sun manages to seep through the grip of the West. It is where the title originates from. But I also found the use of the word “seeping”interesting; the sun could never seep considering that the word is associated with liquids. However, when you write stories you are allowed to turn the sun into liquid if that is what history demands to make your point come across. The stories are in a large part related to the modernization of the whole SWANA region, and a big aspect of it was of course oil, that was seeping through the ground and into foreign pipes. So it is about being in conversation with that also.

Why have you chosen to not translate the stories to Swedish?

Afrang: We always have them in English because it is the language in which Nour and I can communicate and write the easiest together. But it would be fantastic to have them in Swedish since we are exhibiting them in Sweden.